By Pablo Taricco – @tariccopablo

(Editor's note: We rediscovered this in the archives of our friends at NTD,la, who in 2015 published this entertaining piece about a figure worth learning more about, to understand what has happened in our lands. To add a musical element to the reading, we've included the official Spotify playlist at the end of the article.) Andean Indie, (featuring prominent artists from Ecuador, Peru, Colombia, and Chile, whose songs add the right energy to the reading of this good story).

Four $100 bills, or a credit card. 1252 soles will also do to board the Hiram Bingham, the luxurious PeruRail train that takes us from Cusco to Aguas Calientes, the town closest to the breathtaking Machu Picchu. The journey is, of course, an extraordinary experience through the beautiful landscapes traversed by that sophisticated machine of British and Peruvian capital. The journey obviously has its cost, but more than one wealthy gringo recommends experiencing it before leaving Latin America for other exotic landscapes.

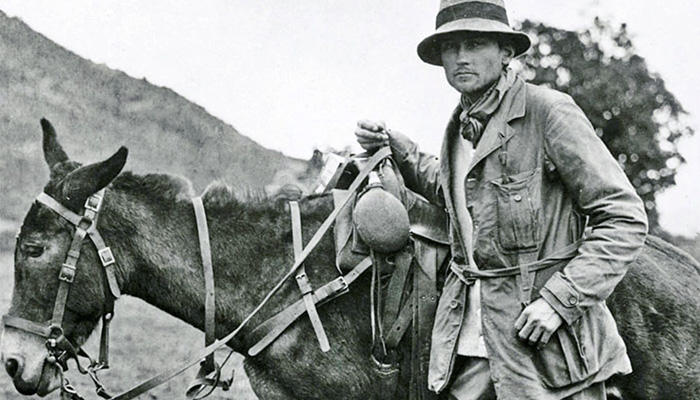

However, when Hiram Bingham He first arrived at Machu Picchu in 1911 on foot, accompanied by only a handful of guides and collaborators. That 35-year-old professor of Latin American history at Yale University had traveled across our continent seeking to deepen his studies on the Liberator Simón Bolívar. But fate had another adventure in store for him. During a trip to Peru in 1909, initially planned to travel the Bolivarian routes on horseback, he learned of expeditions organized by Cuzco authorities in search of the mythical Vilcabamba, the city where the last Inca Emperor unsuccessfully faced the conquistadors. And although he declined the invitation at that time, He began planning his own expedition, which he would finally carry out in 1911.

In mid-July of that year, he ventured into the jungle with his small team. Riding donkeys, they traveled through the Urubamba River canyon until they reached the area known as Mandor. There, an indigenous man named Melchor Arteaga led them for 50 cents to an area where they might find Inca ruins. Bingham knew that he wouldn't find Vilcabamba in that part of the jungle; it had to be further along. But he decided to explore the place Arteaga recommended anyway. It was midday on July 24, 1911 when they set foot on Machu Picchu.

At first, Bingham didn't grasp the significance of the discovery. He took some photos, made notes about the site, and drew some sketches of what appeared to be a citadel hidden in the undergrowth. Then he returned to the camp and the next day continued the search for the Lost City. The expedition lasted several months and yielded positive results. Bingham had also reached Choquequirao and Espíritu Pampa, two archaeological treasures that had sparked speculation about whether or not they were the long-sought Vilcabamba. Toward the end of the year, he returned to the United States to plan his next steps. He had no money left and it was time to share his discoveries.

The National Geographic Society He was immediately interested in his photographs, and proposed contributing $10,000 to return to those ruins that Bingham had named Machu Picchu, according to Arteaga. The goal was to create a large photographic report about the site for publication in their magazine. The same was also contributed by Yale University, and finally his wife, daughter of the owner of the important jewelry store Tiffany From New York, he did the same so that in 1912 Bingham would return for the second time to that citadel that would later be called “The Sacred City of the Incas.”.

In 1913, the anniversary issue of National Geographic It was dedicated exclusively to Machu Picchu. At the beginning, the editor said:

“We, the members of the Society, are extremely grateful for the splendid record made by Dr. Bingham and all the members of the expedition, and as we study the 250 wonderful pictures printed with this report, we too are thrilled by the wonders and mysteries of Machu Picchu. What extraordinary people the builders of Machu Picchu must have been! Who constructed, without steel implements, and using only hammers and stone wedges, the marvelous mountaintop refuge city!”.

That publication was a success. It had managed to place Bingham's discovery at the forefront of scientific debate.

In 1915 the already famous Professor Bingham returned to the site for the third time, This time, he was accompanied by a large group of scientists ready to clear away weeds, excavate, classify, and study in depth that citadel that everyone was talking about. His “discovery”—as he presented Machu Picchu—had placed him in a prominent academic position, and his reputation as a brave and daring explorer completed an ideal picture of opportunity for the 40-year-old scientist. His life was an adventure novel. Meanwhile, Peruvian authorities allowed him to remove 46,000 archaeological pieces from the site, which would be studied at Yale University., to deepen our understanding of such important material. The emergence of Machu Picchu in the scientific world was a very significant event that brought pre-conquest Andean culture to the forefront.

However, as time went on, that epic narrative promoted by Bingham and National Geographic began to be relativized: Some evidence and testimonies emerged that called into question the "discovery" designation with which the Machu Picchu matter was presented. Furthermore, Yale University's refusal to comply with Peru's request for the return of the relics for the next 100 years undermined the prestige of those researchers.

First, Peruvian historians explain that Machu Picchu was never “lost”, since it was frequented by the inhabitants of the area. There are even administrative documents in Cusco from previous centuries that mention petitions and claims regarding those ruins, which by the early 1900s were no secret in the city. However, from a scientific point of view, it is acknowledged that Machu Picchu had not been studied., and they credit the Bingham-National Geographic duo with popularizing that citadel, which generated academic and even tourist interest over the years.

But if we're talking about discoveries, There is a curious detail that was omitted from Bingham's accounts of his arrival in the city. According to his son Alfred Bingham in his book Portrait of an explorer, Hiram had noted in his travel log that upon arriving at the ruins he was surprised by an inscription on the stone: “Lizarraga 1902” It said a scribble written in charcoal. Even Bingham himself wrote: “Agustín Lizárraga is the discoverer of Machu Picchu and he lives on the San Miguel bridge.”. In any case, the debate about who arrived at the site first seems to contribute little. Unless, of course, history will remember you with the title of "discoverer of Machu Picchu".

By way of acknowledgment, it is only fair to highlight that venturing into the jungle for months, crossing it on the back of a donkey, walking, climbing and sleeping in the open air with the desire to discover forgotten or unexplored places, It is merit enough to be remembered. It was even enough to inspire adventure films 70 years later. The rest of Bingham's life was a different story altogether; after leaving his scientific career, he became governor of Connecticut and then a Republican senator. He died on June 6, 1956.