By Emiliano Gullo – @emilianogullo

(Editor's note: We've found another gem in the archives of our friends at NTD.la, an incredible story that we hope many people will read. To add some musical color, we've included a playlist full of rock, blues, ska, and punk, which smells and tastes like all the alcohol they can serve in every bar on the continent.).

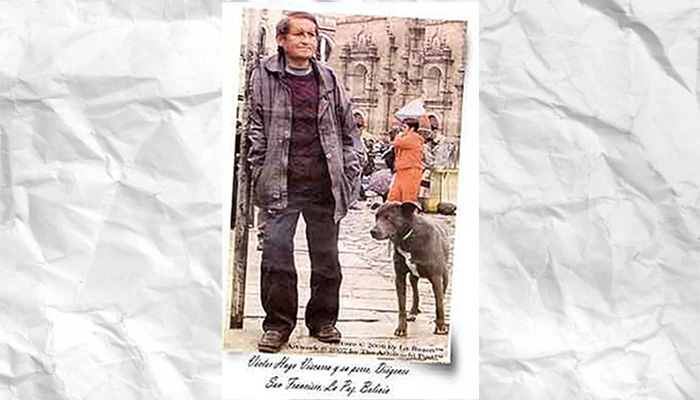

A man lies sprawled in the street. He can barely move, much less speak. A bottle of "Soldadito" rests beside him, its pure alcohol now gone, leaving not even a trace of its scent. The drunkard's name is Víctor Hugo Viscarra, the most mythical and revolutionary writer that Bolivia has ever known. Until the day of his death in 2006, Viscarra made a living from marginalization, alcoholism, drug addiction, sex, and crime., the pillars of a writing style that broke with the literary status quo of his country.

«"I live on the street and I never have any money. I'm a starving poor man. So, what more reality could there be to write about?"», He said in an interview, shortly before dying in La Paz, the same city where he was born on January 2, 1958. His resume states that a few years after his birth he ended up in a children's shelter. Later, he briefly served as a novice in a Catholic seminary until he discovered communism. He joined the Bolivian Communist Party and was a member for years. His formal jobs included positions at the Cochabamba House of Culture and the Customs Office. But he didn't last long in either. His writing had been a driving force since childhood. She also said once that she started writing at age 12 as a way to get rid of family abuse. And later in his life, writing allowed him to assimilate the hardships of the street and transform them into vital energy. “There, with my criminals, my whores, my faggots, my beggars and my thieves, I feel at home.”, he once told journalist Alex Ayala Ugarte.

Regarding his most biographical work –I was drunk, but I remember– Viscarra would regret it shortly after publishing it. “I have tried to free myself from my demons. But I haven’t succeeded.”. On the contrary, I have stupidly reopened wounds that I thought were healed.”. Write in Scars of life, the first story in that book.

“I was born old. My life has been a sudden transition from childhood to old age, with no middle ground. I didn't have time to be a child. There's a brand-new ball, stored away in some corner of my memories. The most logical thing must be that I will be a real child when I reach old age. For her, it's true, one has plenty of time. I presume it must be at forty-nine years old, because if I reach fifty I will commit suicide. "I'll nationalize a gun and shoot myself.".

Later in the same text, he recalls the bond he had with his mother. “She was very nervous, she suffered from a kind of rage. Anything would make her furious, her blood would rush to her head and she wouldn't see anything anymore. Everything would go blurry and the hurricane would begin. He used to hit us with a broomstick. He broke several brooms on my back and my sister's; if we weren't left disabled it was because, they say, children are very resistant to blows.".

In He was drunk, But I remember one of his best-known stories appears, The Elephant Graveyard. Viscarra describes it with intense clarity. “For those who seek to die at the foot of the cannon, That is to say, those who want to commit suicide by drinking nonstop, there's the drinking spree of Doña Hortensia, better known among artists as the Elephant Graveyard”. And then, as if in a supermarket sale, the Bolivian "Bukowski"—an obvious nickname they attached to him—says about the bar:

“The artist who, having decided to commit suicide by drinking, has scraped together enough money for this purpose, may remain in the premises. Not to sleep, but to continue the shenanigans all night long. But he doesn't cast his net in the yard, because instead of dying from poisoning he might end up with a cold, so Doña Hortensia takes the suicidal man into a small room and arranges him there so that he can peacefully end his life.”.

He was two years away from fulfilling his prophecy. At 48 years old, he suffered from rheumatism, chronic pneumonia, digestive disorders, and galloping cirrhosis. On the morning of Wednesday, May 24, 2006, his body was left in a hospital bed in La Paz.